“We’re celebrating them as they go to work and explaining that art is not just a photograph or a sculpture or a painting – it is this choreographed set of balloons as they spread throughout the city.” – US artist, Yazmany Arboleda

“We’re celebrating them as they go to work and explaining that art is not just a photograph or a sculpture or a painting – it is this choreographed set of balloons as they spread throughout the city.” – US artist, Yazmany Arboleda

Minami Sanriku, a former fishing village, was destroyed in March of 2011 by the Tohoku Earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Buildings were completely demolished, cars and trucks were moved from one side of the village to another, friends and loved ones were lost, and survivors are now scarred for life by the significant trauma. How does one overcome these traumas? Perhaps, the process of recovery begins with the ability to share one’s experiences, to speak up, and be listened to. There needs to be a platform or framework developed that allows for a dialogue between speaker and listener. The conversation can be amongst members of the family unit, between friends, or even between survivors and outsiders. Whoever these characters are, there is a voice that needs to be heard, with a story that needs to be narrated, and there is a need to create a platform or an opportunity for where this conversation can take place.

As a member of a group project for the Zones of Emergency course at MIT, I participated in the design of a project that would offer that very framework deemed necessary to allow the survivors to speak up about whatever issues or non-issues they wanted to share. Our proposed framework came to be a sort of ritualistic mapping of narrative. Through the combination of object and passage, we’ve created a portal way into the former village of Minami Sanriku. For one day each year, the people of the village, those who have left and those who remained, will gather at the highest point of the village. At this point, each person will be given a large balloon attached to a string, and at the bottom of the string is a bag filled with a mixture of flower seeds and fertilizer. The bag offers two opportunities: 1. to hold the balloon down as a weight; and, 2. to serve as a tangible marker that gets spread on significant points of memory by the hands of the speaker or survivor.

The process of planting the flower is a mechanical recalling of the person’s individual memories. As the plants begin to grow over the years, these memories become a permanent part of Minami Sanriku’s landscape, giving life to the former landscape that the people of Minami Sanriku cherished and remember fondly. And each year, as the survivors return to these sites and visit their planted flowers, they are able to reflect on the past, while at the same time create a vision for the future. The flowers simultaneously allow for a reflective healing and a resilient hope.

As day turns to night, lights inside the balloons begin to brighten and the large balloons glow. The people of the village continue from point to point, with glowing balloon in one hand, and seeds in the other. They pass from one memory to another – memories from their past, memories of their family’s past, memories of their friends’ pasts. Paths intersect, memories cross, and a collective identity is formed. Through this ritual with objects in hand, a map is produced of Minami Sanriku’s former life and of the collective identity of the village’s inhabitants. Throughout this entire process, a camera overhead captures the creation of this map: streets and paths between new plants are actually strings of thought retracing the steps between memories and newly planted open areas actually represent cherished moments in a person’s life.

At the end of the day’s event, the participants meet at the water front – with bags empty and light-filled balloons in hand. The final product is a moving memory map – a video of the ritual. The map holds in it mobile objects that tell the story of Minami Sanriku as narrated by its own people.

This is our proposed gift to the people of Minami Sanriku – the memory of place, the memory of a past time, and the memory of an identity.

Zainab Salbi is the founder of Women for Women International. A network that provides the possibility for women of war-torn countries to develop relationships through the exchange of letters with women in the United States. These letters offer women who often go unheard in the midst of war with the opportunity to share their stories, and in effect help in the healing process post war. Salbi’s model has proven to be successful, and can be seen as a simple tool that solves the issue of post-trauma silence. I have shared a link to a video of Salbi speaking on TED. The video is lengthy, and I’ve selected two parts that seem relevant to this blog: 8:48-10:36, and 16:36-end. The first segment expresses the duality of war – those who speak at the front line and those who get lost in the back line. It is often those in the back line who have stories to share, but no listeners with whom to share them with. Salbi, with her organization, has given women a simple gift: a friend and listener. In the second segment, Salbi relates her discussion to a quote by Rumi, where he describes a meeting place for the exchange of ideas, “a field.” The field serves as a platform for dialogue, just as Salbi has provided with Women for Women. Enjoy!

Check out this amazing project. How do we make a monument active? I believe this project does it successfully.

With the help of Germany’s then 61 Jewish communities, a list was compiled of all the Jewish cemeteries that were in use in the country before the Second World War. The names of these 2,146 cemeteries were engraved on an equal number of paving stones, which were removed from the alley crossing the square in front of the Saarbrücken Castle, the seat of the Provincial Parliament. Initially, the work was carried out without a commission, in secret and illegally. The stones were removed at night and replaced with engraved ones. All stones were placed with the inscribed side facing the ground and therefore the inscription is invisible. In the course of the project the artwork was approved by Parliament and retrospectively commissioned. Castle Square in front of the Parliament was renamed The Square Of The Invisible Monument (Platz des unsichtbaren Mahnmals).

Object: 2146 engraved paving stones.

Site: Square of the Invisible Monument, Saarbrücken.

In collaboration with students of the Hochschule für Bildende Kunst, Saarbrücken.

Publications:

- 2146 Steine – Mahnmal gegen Rassismus

Hatje/Cantz, Stuttgart 1993 (German)

- 2146 Stones – Monument against Racism

Stadtverband, Saarbrucken 1993 (English)

In response to Jack Persekian’s work, I wondered how far the limits of expression could go in retaliation against injustices without leading to action taken against the artist. I stumbled across the work of artist, JR, who is the recent winner of the TED prize 2011. In the following video, you can see the different areas of the world where JR installs extremely large photographs of people on buildings, houses, roofs, etc. These images portray the very essence of what it means to be human, even in spite of the destruction that surrounds us. In the case of Israel and Palestine – JR put images of Israelis and Palestinians side by side, highlighting the similarities between the two people, rather than constantly showing the differences and each groups individual plight.

JR explains the ease of placing the images in Jerusalem and along the separation wall: “…And you know what, we thought that we would be kidnapped, that we would be arrested, that we would be evicted, and we just came back with sunburns!”

The artwork makes a statement, but does not attack any group or affiliation.

JR – 28 millimeters project – TEDprize winner

Jack Persekian’s controversial work as curator for the Sharjah Art Foundation has stirred conversation in the international art community and has received extreme reactions from the Sharjah government. On one hand Persekian has served the artistic community by fostering an environment that allows for freedom of expression using art as a medium. On the other hand, the collected art also led to the removal of Persekian from his position as head curator for the Foundation. One specific piece called It has no Importance by Algerian artist Mustapha Benfodil, was seen as the “straw that broke the camels back” – because it not only included anti-government sentiments, but was perceived by the general public to blatantly condemn the religion of Islam. Persekian’s reaction to his removal was almost apologetic saying, “he didn’t see the work and implied it wouldn’t have been included if he had” (Donley, 2011).

It has no Importance _ Artist: Mustapha Benfodil

In America we enjoy the freedoms of being able to say whatever we want, whenever we want, and about whomever we want – as secured for us in the United States constitution. However, this freedom is expressed even to the most extreme levels and no official can stop it from happening. It can be condemned, but if it is on your own private property, then you can go as far as you’d like. We often see the desecration of religious books, hear people being verbally abused on the street, or even garbage being thrown at our own neighbors. At times the local police are involved, and a warning is given out to those who have expressed their hatred. But nothing more can be done. Some extreme cases of protest have led to equal or if not worse reactions from those who were being criticized.

There is a constant dance between censorship and freedom of speech. Neither one can be allowed to reach an extreme level. As a curator of an art exhibit, how then do you make the decision of what is permissible to be on display, what has not reached a certain threshold of too controversial?

A creative summit is being held in New York City that celebrates 20 years worth of socially engaged art.

Dates: September 24 – October 16, 2011

Where: Essex Street Market

Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from the Last 20 Years from creativetime on Vimeo.

Music, being a common language, is used by this group to promote peace in a contested area. Al Kamandjati was developed in 2002 by Ramzi Aburedwan teaches music to Palestinian children throughout the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and parts of Lebanon. Teachers from all over the world, meet in this zone of emergency, and provide these otherwise silent protesters, with an opportunity to express themselves through music. Finally, the students have an outlet – a moment where they can forget the war torn area they live in, and enjoy first class lessons in music.

Al Kamandjati Student

Student and Teacher

Students Study Outside

Palestinian Students in Ramallah Playing the Classics

The organization is also clear to point out that after years of political movements towards peace, there has been no success. Al Kamandjati has been successful in its work, and is pushing for another type of retaliation: a cultural movement. Believing that expression through art is just as important as living life itself, Al Kamandjati makes it it’s goal to see that Palestinians receive the same opportunities for a musical education as others throughout the world.

Learn more about this amazing group on their website: Al Kamandjati

An article on Al Kamandjati written in 2008: “Overture to Peace in the Westbank”

In an attempt to dissect and analyze Freud’s discussion of melancholia and mourning, Judith Butler in Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence, addresses this idea of a, “hierarchy of grief.” We live in a society so engulfed in war and death that so quickly decides the value of one human life and so easily dismisses the sacredness of another. Media outlets tend to lump and calculate overseas death tolls for certain regions of the world, and not others. We decide what groups deserve a lengthy broadcast that clearly depicts their loss and touches on our need to grieve alongside our fallen neighbors. Where as other groups are not worthy of the same.

Butler asks, “To what extent have Arab peoples, predominately practitioners of Islam, fallen outside the ‘human’ as it has been naturalized in its ‘Western’ mold by the contemporary workings of humanism? What are the cultural contours of the human at work here? How do our cultural frames for thinking the human set limits on the kind of losses we can avow as loss? After all, if someone is lost, and that person is not someone, then what and where is the loss, and how does mourning take place?”

In an area of conflict, Jerusalem, we often only hear the cries of the Israeli people. Do we not also need to listen to the voices of the Palestinians, who’s homes are being demolished on a daily basis for the expansion of Israeli settlements, or schools are being shut down out of fear of an unstable environment, or who are living in separation from their own family and friends because of a wall put up to keep the evil out and the good in?

The separation wall built up by the Israeli government is now being used as a means of retaliation, and a canvas for artists to share their opinions with the world. Perhaps through the intervention of art in this manner, we begin to give voice to those our own media depicts as un-human. The following are images of the separation wall, and a news clip on guerrilla artist, Banksy, who uses the separation wall to speak out: Banksy – News Clip

Apartheid Wall cutting through Abu Dis, Palestine

Banksy_Palestinian Ladder

Banksy Art

Shifting gears to a more local zone of conflict…

In the case of memorial structures, who is the design targeting? Memorials have just been completed and made public for the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center, in New York, the Pentagon in Washington DC, and the site of Flight 93′s crash in Shanksville, Pennsylvania. Do these memorials allow for the mourning of only those attacked on that fatal day, or do they also allow for reflection of the destruction that came after the initial attack: American soldiers who lost their lives in this war on terror, innocent Afghan children who died along side their mothers and fathers, or thousands of casualties at home and abroad who live everyday with physical and mental side effects of the terrorist attacks as well as the American-led war.

The memorial in Shanksville, PA clearly portrays a hierarchy in its own design. The design team, Paul Merdoch Architects, clearly delineated areas that were more sacred, and those that were more mundane. The mundane was accessible to the public as a whole, while the sacred area, where Flight 93 actually hit earth, was only made available to the families of those who passed (and superior officials like the President). For the rest of us, we could only mourn and reflect on the loss of the fallen from behind a wooden gate some distance away. What does this separation do to the collective community in the process of mourning and healing? Does the separation make it difficult for the public to reflect on the impacts of that day on a more grand scale – beyond that sacred, untouchable site, and extended abroad to other sites of emergency and destruction? Or is that reflection only reserved for a small group of people?

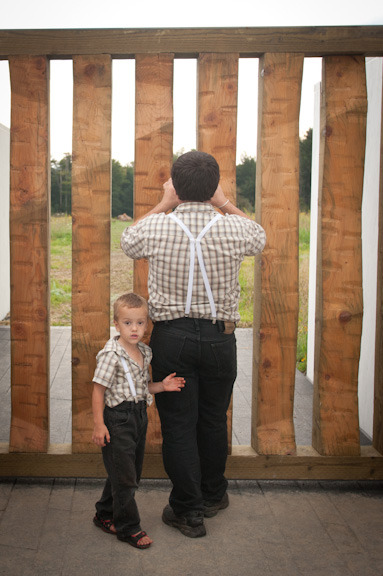

Ceremonial Gate, Flight 93 Memorial, Shanksville, PA

Boulder marking the crash site_on guard.

President Obama and his wife_on sacred grounds.

In the midst of conflict and in the time after a crisis, who do we decide is worthy of mourning or human enough to grieve? As artists and architects we must provide intervention that speaks to the collective, that does not give way to this world of politics, but rather provides a platform for discussion and policy transformation.