This is a cross posting from Network for Historical Materials, 09/04/2011

By Ikuyo Numura, a secondary school teacher and a researcher of the medieval history and women history

I still remember the stains whose colours were just like the strawberry and lemon syrup.

I participated in the voluntary operation in the secretariat office of the Miyagi Network for Preserving Historical Materials in Tohoku University, Sendai City from 8th to 9th of August.

On the morning on 8th, I headed to the Centre for Northeast Asian Studies by bus which was full of students who weren’t on summer vacation yet, but I couldn’t reach there because the building was surrounded by the fence. I had never thought that the building was closed due to the damage by the quake, and the secretariat office had already moved to another building’s top floor where we can see a splendid landscape.

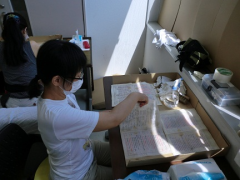

In the secretariat office, the damaged historical materials were transferred from each area in Tohoku. The operation which I was involved in was cleaning, so I removed the mould from documents waterlogged by the tsunami, and sprayed the ethanol in order to disinfect them. The historical materials were contemporary ones, from at least 50 years ago, however they were difficult to deal with because they didn’t have much strength the same as the Japanese paper had.

Although now was already 5 months after the tsunami, the documents were still wet, and it was hard to separate them one by one, because the paper was really thin. Usually it was said that the materials which were once soaked be seawater cannot get mould easily though, if left for a long time the mould would occur here and there. The mould was, I don’t know why though, somehow very beautiful, as if the pink and yellow water drops were scattered.

When I sprayed the ethanol onto the papers, in a moment, they were soaked and became transparent. This meant that the roots of the mould were cut off, and the process of my operation was basically at an end. After that, the only thing I could do was to wait for drying them.

We carried out such operations in silence from 9am to 5pm. Those operations never affected us, moreover we concentrated on this work very much. However, time passed by in the twinkling of an eye, and those materials which we could completely finish numbered very few. Nevertheless, we could find fulfilment in our work. After finish the operation, we enjoyed the tasty seafood dinner, and comfortably came back to our accommodation.

However, I got up at late night because I dreamt something horrible. It was very rare for me, so I think I was under strain and really tired of the operation. Probably, this work was tougher than I had thought.

The secretariat officers seemed to be extremely busy; they responded to the interviews by the mass media who suddenly visited the office, instructed the voluntary workers and gave them orders, managed the time balance between work and break, as they coped with their original work. If they had some spare time, they came to the workshop area where we carried out the operation, and joined us to clean the damaged documents. I think their work was really tough. Although they were busy, they offered us watermelons and looked after us very kindly, therefore we could work comfortably.

The members who worked together were active women living in Sendai, and they talked about the nice restaurants in the city or the experiences in the disaster in a casual manner. I could spend a meaningful time because of them. Furthermore, I was deeply impressed by the sincerity of the postgraduate students who came to join the voluntary work rushing by the highway express bus from faraway places.

If I can have another opportunity, I want to participate in this operation. I’d like to express my gratitude to the secretariat officers.

NB: The photos are all from the homepage of the Miyagi Network for Preserving Historical Materials.